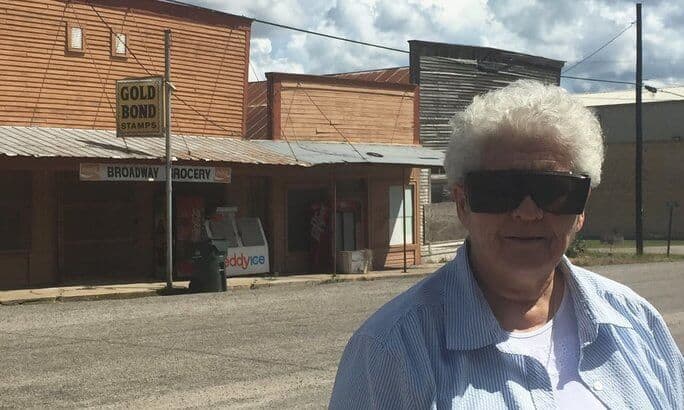

Sister on a mission: the Texas nun using oil company money to fight fracking.

Sister Elizabeth Riebschlaeger, 80, funded by mineral rights fees on a family property, is backing a campaign against fracking in the sleepy town of Nordheim

“I call it redeeming the money,” said Sister Elizabeth Riebschlaeger, munching a turkey sandwich in a bar with a stuffed steer’s head mounted on a wall next to a life-sized poster of John Wayne.

About six years ago, when fracking got feverish in the Eagle Ford Shale, a company offered to lease the mineral rights to some land bought by her grandfather in the 1920s.

Sister Elizabeth did some research about the consequences of fracking – extracting natural gas by pumping water, sand and chemicals at high pressure into wells deep underground – and did not like what she learned. But her attorney told her that the company would find a way to get the rights with or without her consent.

She decided: “What I’ll do is I’ll take the money and use it for something that will promote responsible development.”

The nun would donate her oil and gas windfall to fund watchdog activities, holding the oil and gas industry to account and warning of the dark effects of get-rich-quick, lightly regulated capitalism.

The 80-year-old roams the region, educating, advocating and sniffing out malpractice, often in a white Honda Civic with more than 250,000 miles on the clock, a windscreen that keeps getting cracked by road debris kicked up by trucks, and bumper stickers that say “Don’t Mess With Texas” and “No Disposal Pits”.

As a result of her vow of poverty, the proceeds from Sister Elizabeth’s mineral rights go to her Catholic congregation, the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word of San Antonio, which funds her tours.

Sister Elizabeth is backing a long-running, longshot campaign to stop a fracking waste pit from being built next year in fields just outside the city limits of Nordheim, only half a mile from the main drag and a school with about 170 pupils. It’s an eye-catching battle in the Eagle Ford, which runs for some 400 miles through south Texas from the border with Mexico through to counties north-west of Houston.

“With the onset of the fracking we had hectic, frantic activity. Everybody was rushing to get those wells drilled,” Sister Elizabeth said.

“Air quality and safety deteriorated a great deal. Lots of people were killed on the roads.”

A boarded-up building in downtown Nordheim. Photograph: Tom Dart for the Guardian

The first well of the Eagle Ford Shale boom was drilled in 2008. That year, 26 drilling permits were issued. In 2014, the height of the frenzy, the figure soared to 5,613. Amid the industry’s continuing downturn, 642 permits were issued from January to August this year.

A landscape of cattle ranches became blotched with well pads. As vehicles barreled along once-quiet country roads, fatal traffic accidents in the region increased by 40% between 2011 and 2012.

“One man’s American dream quickly becomes another man’s American nightmare,” Sister Elizabeth said. “All you have to do is drive around and you will see the damage being done to the environment. And I point those things out and tell people that it can be reported.”

The rapacious pace of the fracking surge and the stress the process puts on the environment is hard for some to digest, even in a pragmatic and conservative state that owes much of its prosperity and population growth to oil.

“We didn’t even water our lawns in droughts. Now we see it going out by the truckload so people can waste it by putting it down a hole,” said Lyn Janssen, whose bucolic ranch is a short drive along the same country lane as the planned dump.

While other places nearby have grown and smartened up by exploiting the boom’s economic benefits, Nordheim has stayed sleepy. Folks whose families have been here for generations and want a quiet rural retirement like it that way. Which may help explain why, unlike its neighbours, little Nordheim, population 307, fought back.

At the least there will be a substantial increase in industrial traffic. At worst, locals fear that the pit and landfill cells will stink and release toxic chemicals into the air and the ground. At 143 acres, the facility will be roughly half the size of the town.

Federal rules allow a maximum leakage rate of 100 gallons per acre per day from disposal cells and 1,000 gallons per acre per day from pits. Then there are concerns about the potential for leaks and spills. An underground gas pipeline runs through the site. It ruptured in 2014 only a stone’s throw away and contaminated soil.

“Within five years, if it’s put in, this town will die,” predicted Larry Baucum, seated behind the counter at Nordheim Mercantile, a bric-a-brac bazaar in town. In the window, next to a sign stating the opening hours – three days a week – there is a poster with a skull and crossbones and the slogan “Don’t Dump on Nordheim”.

He believes that businesses and residents would flee. “It’s not that we’re against the pits – I’m an old oilfield hand,” the 69-year-old said. “But we’re against the location. It does not have to be right next to our city limits.”

A posse of Nordheim residents banded together and formed a group called Concerned About Pollution (CAP). Armed with technical knowledge and a stubborn streak, they wrote letters, showed up at hearings in Austin and managed to stall the granting of a permit for three years.

Their battle ultimately underlined the limited powers of the state’s oil and gas regulator, the anachronistically named Texas Railroad Commission, which has often drawn accusations that it enjoys an overly warm relationship with the industry it oversees.

When the permit was confirmed in May, the developer, Petro Waste Environmental, said in a statement that “high standards of safety and compliance are Petro Waste’s top priority. These core company values played a vital role in the design and engineering process for this facility.”

Paul Baumann in front of the planned waste site near Nordheim. Photograph: Tom Dart for the Guardian

CAP did not admit defeat: it filed an ongoing lawsuit in Austin to challenge the decision. But victory appears unlikely.

CAP’s president, Paul Baumann, was born in Nordheim and owns a rental property next to the site. His brother and nephew live close to the entrance. The 72-year-old returned after a career working at a DuPont chemical plant near Houston.

“Thought I was gonna be away from chemicals and breathe my clean air down here,” he said ruefully before guiding his pickup truck down a bumpy path next to the future dump along a hayfield dense with dancing butterflies.

“It’s a terrible site,” Sister Elizabeth said. But her indefatigable crusade against “capitalism without moral or ethical values” in the Eagle Ford Shale goes on.

Original Source: The Guardian.

On the header: Sister Elizabeth Riebschlaeger in downtown Nordheim: ‘I call it redeeming the money.’ Photograph: Tom Dart for the Guardian.

0 Comments